“While the ‘rule of law’ appears to enjoy favor as a universal prescription for political justice and a key pillar of constitutional government, ‘higher law’ has fallen out of fashion. Contemporary expositions of the rule of law rarely refer to a higher law, favoring instead a laundry list of legal rules and institutions considered necessary to realizing the rule of law. The rule of law is variously conceived as a negative or ‘thin’ ideal, designed to promote limited government, clear rules, and due process, or in more ambitious ‘thicker’ versions, as a concept that embraces the essential moral content and purpose of law. What all conceptions share in common is that they are against autocracy and arbitrariness in the exercise of public power. But if the rule of law is to be an idealized standard against which positive law is evaluated, this begs the question whether it can be thought of and implemented without the concept of a higher law, as the substantive source of principles to which the rule of law must conform.

“This was not problematical for Hellenic and biblical streams of Western legal thought, which drew an explicit link between a higher law and the rule of law. Historically, the higher law was rooted in the divine law and natural law traditions. This provided an objective reference point for evaluating and even voiding inconsistent laws at the lower rung of the legal hierarchy, a higher law over rulers and ruled alike. However, the idea of a higher law has come under siege in an era of legal positivism, legal realism, and postmodernism, which decries ‘grand theory’ and insists that law is not a province autonomous from politics. As such, ‘law’ departs from ‘the realm of jurisprudence and philosophy’ and takes up residence in the ‘domain of politics’ where it becomes a tool to advance particular ideological agendas. As the rule of law is shaped by the conception of law upon which it rests, we find that the thicker its vision, the more controversial it becomes.

“The rule of law has attained something of the status of an ‘international hurrah term,’ or what E. P. Thompson described as an ‘unqualified human good,’ because it defends citizens from ‘power’s all-intrusive claims.’ Nonetheless, the idea remains an ‘essentially contestable concept’ as the many proliferating, competing accounts of rule of law attest. . . .

“Christian theology gives rise to a teleological view of the ‘law,’ where law does not just cater to a ‘liberalism of fear’ but also channels power to accomplish certain objectives or to constitute the identity of a civil polity in service of the divine will. The moral law of God, which reflects his character as a relational, covenant-making God, will inform the content of moral and legal rights. The functions of law go beyond ‘command and sanction’; law has symbolic and educative functions in expressing deep values and shaping communal identity. As man is created imago dei, and as God is the supreme lawgiver, man in creating constitutions reflects an aspiration imitatio dei. Augustine characterized the ‘three forms of the triune God’ as will, reason, and memory This is reflected in the three corresponding elements one finds in every constitution: power, justice, and culture.

“Several key facets of the rule of law shaped by a Christian vision of the higher law can be identified. On this view the essential purpose of positive law is to ‘make higher law effective in human living,’ thus realizing liberty, justice, the common good, and shalom, a state of peace and relational well-being. It speaks of legitimate and limited government, established by God to do good for citizens, protecting them against abuses and punishing the wicked (Rom. 13). The rule of law requires the state to prove its powers and stay within its limits. Part of the common good is securing public order and guarding against despotism, as the biblical understanding of man is that he is sinful and susceptible to corruption and abuses of power. Men are not angels, and modern constitutionalism has devised checks and balances based on principles with widespread currency, such as the rule of law, separation of powers, and subsidiarity to allocate, diffuse, and regulate power. The rule of law as a form of accountability addresses the fear of the unbounded discretion of regulators and prosecutors.

“The first facet of the rule of law shaped by a Christian vision is that all human government should be below and not above the law, that is, Lex Rex, rather than Rex Lex. Henri De Bracton, the father of the common law, stated that the king was subject to God ‘for he is not truly king, where will and pleasure rules, and not the law.’ All authority is from God, and those he delegates it to must serve his purposes. Owing to man’s sinful nature, no one should wield unlimited authority and governors should be subject to external restraints. Civil authorities are to respect the supremacy of God’s higher law over state law, as positive law that is unjust is a ‘corruption of law.’ Ockham considered that ‘any civil law which is repugnant to divine law or manifest reason is not law,’ as the lex divina/lex dei ‘overrules contrary human law no matter by whom promulgated.’ . . .

“[T]hose who adjudicate should not be partial, but judge fairly between rich and poor alike (Lev. 19:15). This principle supports the constitutional prescription of an independent judiciary and judicial review as an engine of the rule of law under which public officials are subject to judicial control in the exercise of their official discretion. Furthermore, they should observe rules of natural justice, as God did in Eden with humanity, giving a fair hearing and a reasoned opinion for his judgment (Gen. 3:9–13).”

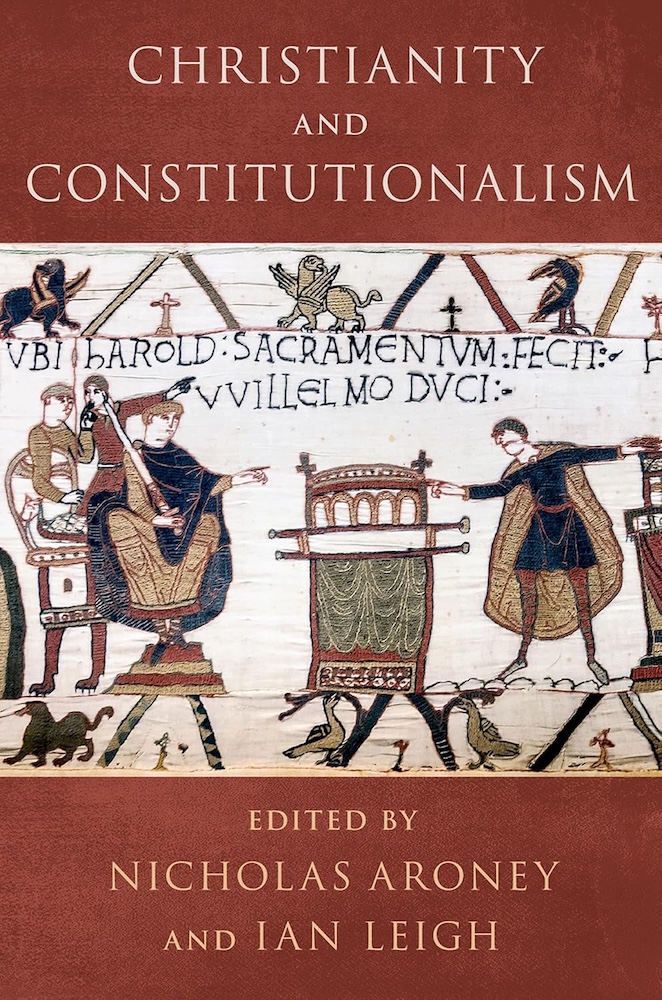

— from Li-ann Thio, “Rule of Law: The Sacred Roots and Secular Shoots of the Supreme Law,” in Nicholas Aroney and Ian Leigh, eds., Christianity and Constitutionalism (Oxford University Press, 2022)