“Many have deplored the effects of entertainment and celebrity on America, and there is certainly much to deplore. While an entertainment-driven, celebrity-oriented society is not necessarily one that destroys all moral value, as some would have it, it is one in which the standard of value is whether or not something can grab and then hold the public’s attention. It is a society in which those things that do not conform — for example, serious literature, serious political debate, serious ideas, serious anything — are more likely to be compromised or marginalized than ever before. It is a society in which celebrities become paragons because they are the ones who have learned how to steal the spotlight, no matter what they have done to steal it. And at the most personal level, it is a society in which individuals have learned to prize social skills that permit them, like actors, to assume whatever role the occasion demands and to ‘perform’ their lives rather than just live them. The result is that Homo sapiens is rapidly becoming Homo scaunicus — man the entertainer. . . .

“Entertainment was first and foremost about the triumph of sensation over reason. Nineteenth-century America was largely about the triumph of democracy over oppression. The fit between the aesthetic and the social could not have been more perfect. When these linked, they posed a formidable force that not only swelled the amount of entertainment but supported it against elitist attack. Because of this alliance, popular culture would become the nation’s dominant culture. Because of this alliance, America would henceforth be a Republic of Entertainment. . . .

“[T]he various forms of entertainment, including television, were only shadows on the wall of the cave. What made entertainment a cosmology was the constellation of expectations that these shadows created, expectations that would weigh heavily on the American consciousness and change our mental architecture. Though it was hardly the only factor, entertainment of all sorts had helped inspire — and would benefit from — what Vanity Fair editor [Francis Welch] Crowninshield approvingly described in 1914 in his magazine’s inaugural issue as an ‘increased devotion to pleasure, to happiness, to dancing, to sport, to the delights of the country, to laughter, and to all forms of cheerfulness.’ Because pleasure was so pleasurable, this attitude had led in turn to an expectation that everything should provide pleasure if only because anything that did not would very likely be shoved aside by something that did. That power of expectation had led in turn to a power of conversion in which more and more of American life would come to resemble entertainment in order to survive.

“Yet all this was inchoate until the movies arrived to galvanize it. As the most powerful form of entertainment, the movies were also the most powerful agents of its cosmology, and long before television, they had become the central metaphor for American life. What the movies provided, early critics like Jane Addams realized, was a tangible model to which one could conform life and a standard against which one could measure it, both in seemingly trivial ways, like fashion or behavior, and in more serious ways, like the movie-induced expectations one had about the course of one’s own life or the value of one’s own deeds. Why can’t life be more like the movies? viewers asked, and then answered that it could. . . .

“[E]ntertainment and consumption were often two sides of the same ideological coin. Entertainment was about release, freedom, transport, escape. Aside from the purchase of necessities — brands of which were themselves often differentiated from one another by their ‘personality’ — so too was consumption. Entertainment was about the power of sensation. So too was consumption, in this case the sensations generated externally by how one looked and internally by how one felt. Entertainment was an expression of democracy, throwing off the chains of alleged cultural repression. So too was consumption, throwing off the chains of the old production-oriented culture and allowing anyone to buy his way into his fantasy. And, in the end, both entertainment and consumption often provided the same intoxication: the sheer, mindless pleasure of emancipation from reason, from responsibility, from tradition, from class and from all the other bonds that restrained the self.”

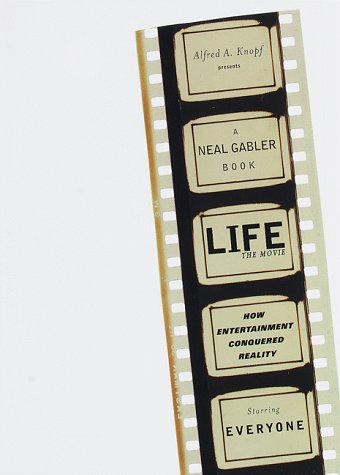

— from Neal Gabler, Life the Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998). Neal Gabler discussed his book on Volume 39 of the Journal, an interview resurrected on the Friday Feature for February 14, 2025.