[Below is the script for the Friday Feature

from December 22, 2023.]

This is the Friday Feature for December 22nd. I’m Ken Myers.

Listeners may know that for a number of years, I’ve been serving as music director at my church, All Saints Anglican Church in Ivy, Virginia, just outside Charlottesville. This time of year is typically a busy time for church musicians, and the repertoire of choral music composed for singing during Christmastide is amazingly rich.

Since I was in high school, I’ve been collecting albums of Christmas music, first on vinyl, later on CD, then digital-only albums. Currently, all of that music is available from my computer, and according to the music app that manages the collection, if I wanted to listen to all of it, it would take 10 days, 20 hours, 18 minutes, and 40 seconds.

Of the many recordings of Christmas music in my library, relatively few of them feature music by a single composer. Most are anthologies of works by a variety of composers and arrangers: carols, motets, chants, anthems, and extracts from Christmas cantatas or oratorios. But one composer stands out as a notable exception: Michael Praetorius. I have at least five recordings in my collection that concentrate on compositions and harmonizations of Christmas (and Advent) music by this great (if under-appreciated) late Renaissance composer.

Just last Sunday, the third Sunday in Advent, my choir sang a six-part piece by Praetorius based on the melody linked with the German Advent hymn, Nun komm der Heiden Heiland, “Now come, Saviour of the heathen.” The text is Martin Luther’s adaptation of an Advent hymn attributed to St. Ambrose, Veni redemptor Gentium. It was first published in one the first Lutheran hymnals ever printed, in 1524. And the tune that Luther chose to be used with that text was one that he adapted from a plainchant melody long associated with Ambrose’s hymn.

You may know the Lutheran chorale melody and an English translation of his text in the hymn, “Savior of the Nations come,” which is included in many modern hymnals. Here’s organist Michael Ebert playing that chorale, from an album of Christmas music by the ensemble Stimmwerck.

MUSIC

When Michael Praetorius got hold of the text and tune, like many before and after him, he created several different settings, including the one we just sang last week. Here’s the Cambridge Bach Ensemble with the opening measures of that setting.

MUSIC

That’s from an album of early Lutheran choral music titled The Muses of Zion, which also includes a 4-part setting of Praetorius of this chorale.

Twentieth-century pastor and Musicologist Walter Blankenburg expresses a consensus among his colleagues in proclaiming that Praetorius (1571–1621) was “the most versatile and wide-ranging German composer of his generation and one of the most prolific, especially of works based on Protestant hymns.” In his first published work, Musae Sioniae (“The Muses of Zion,” in nine volumes, published between 1605 and 1610), Praetorius presented 1,244 compositions which explored various methods of setting Lutheran chorale melodies, which were the backbone of Protestant liturgical life. These and other works earned him the title “conservator of the chorale.”

Conductor and scholar Peter Holman contrasts the achievements of Praetorius with those of the better-known Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672): “While Schütz was writing freely for an expert court ensemble in an idiom derived from Gabrieli, Praetorius devoted himself to marrying the Italian Baroque style to the Lutheran chorale, and to writing music that could be performed, if necessary, by the humblest village choir.”

You probably don’t live in a village, but it’s likely that you’ve experienced a church choir or even a congregation singing Praetorius’s 1609 harmonization of the fifteenth-century German folk carol Es ist ein Ros entsprungen (variously translated as “Lo how a rose e’er blooming,” “I know a rose-tree springing,” “A spotless rose,” etc.).

MUSIC

The delicacy and quiet confidence of the harmonic movement in this work echoes the imagery of the Christ-child as a fresh and vulnerable flower.

Almost as familiar are Praetorius’s numerous settings of an even older (thirteenth century?) and more robust Christmas hymn, In dulci jubilo, a melody most associate with the words “Good Christian men, rejoice!” Praetorius’s arrangements have been recorded by countless ensembles, some of them with intricately intertwined a capella voices, some with large choirs augmented by jubilant brass and organ.

A splendid example of the former, more intimate In dulci jubilo can be heard on a 1999 album entitled Praetorius: Puer natus in Bethlehem — Renaissance Christmas Music, sung by the ensemble Viva Voce. Their performance weaves together three different arrangements by Praetorius of this simple tune. On of these features three sopranos and a tenor.

MUSIC

Like the sixteen other pieces on this quietly delightful recording, the vocal clarity of this six-voice ensemble brings out the subtle harmonies Praetorius lovingly constructed.

The text of In dulci jubilo was traditionally believed to have been taught by angels (the muses of Zion) to a German Dominican monk named Heinrich Seuse (c.1295-1355). Herr Seuse had been a student of the great mystic Meister Eckhart, and in 1328 published a book called The Little Book of the Eternal Wisdom, which contains numerous accounts of visionary experiences and visitations, the author always referring to himself in the third person as “the Servant.” In one of these accounts, a group of angels in the form of a youth and his fellows visited the Servant, sent from God

to bring him heavenly joys amid his sufferings; adding that he must cast off all his sorrows from his mind and bear them company, and that he must also dance with them in heavenly fashion. Then they drew the Servant by the hand into the dance, and the youth began a joyous song about the infant Jesus, which runs thus: “In dulci jubilo,” etc.

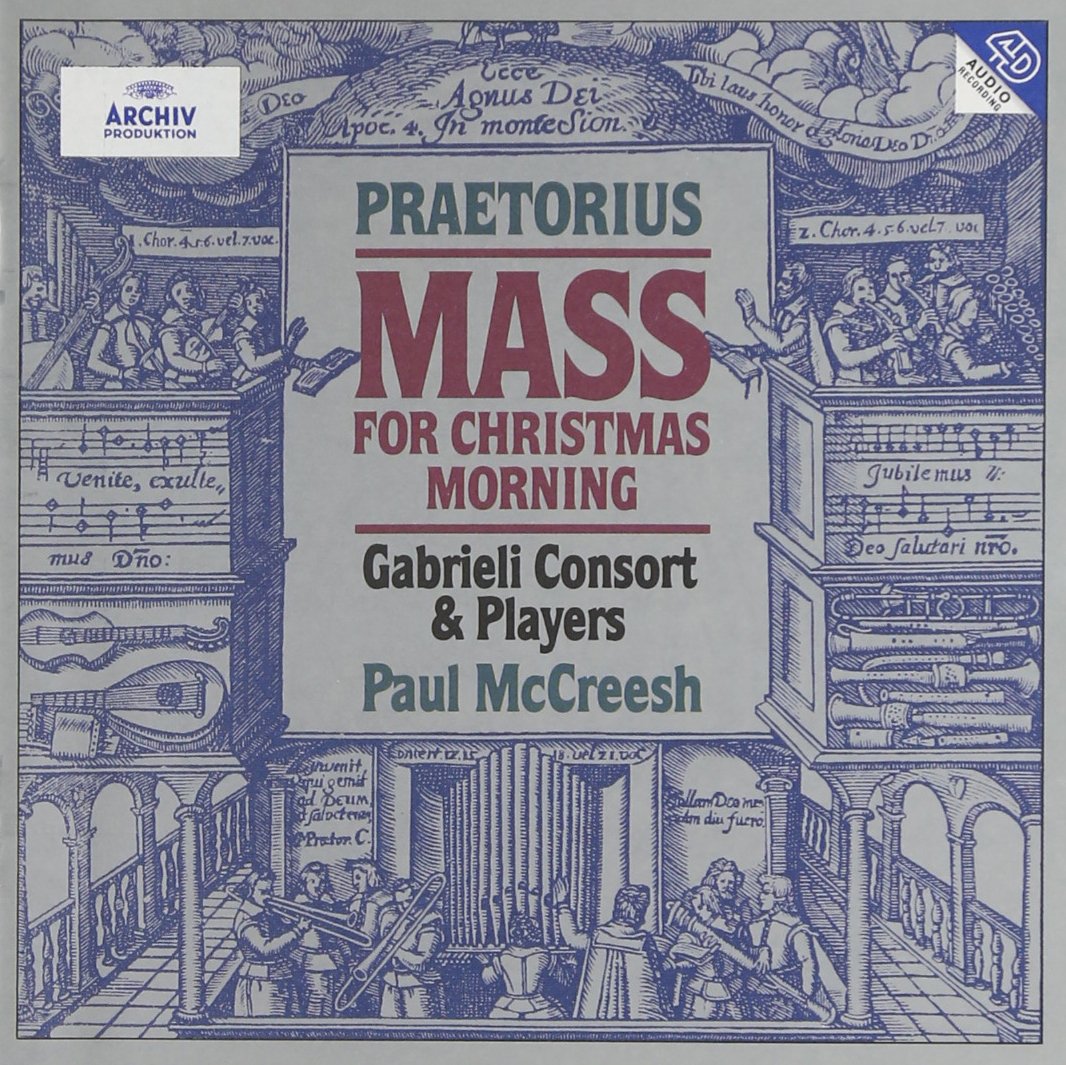

If the setting of In dulci jubilo sung by Viva Voce displays the quietly joyful capacities of Praetorius’s versatile skills, the setting sung on the 1994 recording Praetorius: Mass for Christmas Morning reveals a composer who also imagined heavenly choirs in their most glorious and spectacular mode. Working from a 1619 score for four choirs, six trumpets, and drums, the Gabrieli Consort and Players, conducted by Paul McCreesh, have added strings, woodwinds, and organ to the mix. (This is in keeping with Praetorius’s description of his composing “for choirs of voices, organs, and other instruments.”)

All the stops are appropriately pulled out for the final stanza of this hymn to the infant Jesus, understood not merely in the humble setting of a Bethlehem stable, but in a more cosmic context:

Where are joys more deep than heaven’s are? In heaven are angels singing new songs, in heaven the bells are ringing in the courts of the King. O that we were there!

MUSIC

This thrilling performance is the final track in an album that McCreesh describes a “a selection of Praetorius’s music as it might have been heard at a Lutheran mass for Christmas morning celebrated at one of the major churches in central Germany around 1620.” McCreesh’s ambitious liturgical reconstruction begins in a much more austere register with an a capella processional, a four-part setting of Christum wir sollen loben schon (“We now must praise Christ”), one of Martin Luther’s many translations/paraphrases of pre-Reformation hymns. Based on the fifth-century A solis ortus cardine, traditionally sung at lauds on Christmas Day, this eight-stanza hymn appeared in the first Lutheran hymnbook in 1524.

While Praetorius wrote at least two settings of this hymn, McCreesh has selected for this recording a score by Lutheran pastor and theologian, Lucas Osiander (1534–1604).

MUSIC

This processional is followed by an Introit, Praetorius’s 1619 Puer natus in Bethlehem (“a Boy is born in Bethlehem”), an intricate three-choir arrangement of one of the most venerable of Christmas songs.

MUSIC

In addition to his musical compositions, Michael Praetorius is known for the treatises he wrote in which he developed a sophisticated theology of music and liturgy, including a principled defense of the use of instruments in church services, which was a contested issue among heirs of the Reformation).

I hope you can make time during Christmastide to enjoy some of the gifts that Michael Praetorius has given the Church. In addition to the two recordings mentioned here dedicated to his Christmas music, albums from the Bremer Barock Consort, Apollo’s Fire, and the Westminster Cathedral Choir are also worth your attention. Thanks to Michael Praetorius, you will soon find yourself joining in song with cherubim and seraphim and all the company of Heaven. Listening to the music is much better than listening to me talk about it.

That’s all for this week. Merry Christmas. I’m Ken Myers.

For reviews of twelve selected albums of Christmas music,

see this post at canticasacra.org.