“‘Limits,’ as Christopher Lasch said, was one ‘unifying thread‘ in the narrative of the last book he published in his lifetime, The True and Only Heaven. (The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy and Women and the Common Life were published posthumously.) He sought in this book to reconstruct a tradition that ‘runs against the dominant currents in modern life but exerts considerable force, even today.’ This sensibility was one that called into question the prevailing dogma of unlimited progress, ‘the promise of steady improvement with no foreseeable ending at all.’ This dogma — which Lasch insisted afflicted both the right and left ends of the political spectrum — happily ‘makes it unnecessary to raise the question that haunted our predecessors: how should nations conduct themselves under sentence of death?’

“But, Lasch pointed out, modern industrial nations could no longer be confident that they were free of such a death sentence. Global warming and other environmental crises had put it back on the table, and ‘the fact remains: the earth’s finite resources will not support an indefinite expansion of industrial civilization.’ The task Lasch set for himself in this book was to present an opposing strand of counter-progressive thinking in the American and European past with which to inform a contemporary sensibility ever alert to the limits on human being-in-the-world.

“Of course not only nations but individuals had to conduct themselves under a sentence of death. As Martin Heidegger forcefully argued, human being-in-the-world (Dasein) is defined by a conscious awareness of its eventual death. Human beings are those beings who as they live know that they are going to die. It is the height of inauthenticity to evade this fate.

“Lasch observed in 1979 that proponents of unending ‘improvement’ were all too ready to evade, or even deny, this seemingly undeniable limit to human experience. They were thereby making significant contributions to what he famously termed ‘the culture of narcissism.’

“A culture of narcissism is a culture wholly of the present, one cut off from the past and, as a consequence, from the future. (The working title of The Culture of Narcissism was, at one point, Life Without a Future.) It is, among other things, a culture engaged in a determined campaign against old age, ‘which holds a special terror for people today.’ Concern about old age is understandable, to be sure, but Lasch found his contemporaries to be in an ‘irrational panic’ about it. He attributed this fear to a loss of ‘the traditional consolations of old age.’ Above all it reflects an absence for the narcissist of the solace to be found ‘in the belief that future generations will in some sense carry on his life’s work. Love and work unite in a concern for posterity, and specifically in an attempt to equip the younger generation to carry on the tasks of the older.’

“Generational links essential to an interest in the future so defined had frayed in contemporary American society to disastrous effect. ‘Late capitalist culture’ had occasioned ‘people to lose interest in the young and in posterity, to cling desperately to their own youth, to seek by every possible means to prolong their own lives, and to make way only with the greatest reluctance for new generations.’ Absent deep trans-generational bonds, Americans were sacrificing the future to a prolonged and even perpetual present, rendering the ‘future’ little more than time hence. ‘Narcissism,’ Lasch said, ‘emerges as the typical form of character structure in a society that has lost interest in the future.’ Fear of old age and death is a self-absorbed terror at the thought of supersession. ‘When men find themselves incapable of taking an interest in earthly life after their own death, they wish for eternal youth, for the same reason they no longer care to reproduce themselves. When the prospect of being superseded becomes intolerable, parenthood itself, which guarantees that it will happen, appears almost as a form of self-destruction.’

“At its extremes this campaign against old age has rendered it a simple medical problem, one that enthusiasts declare is ‘something doctors may someday hope to do something about.’ Thinking about aging has fallen into the hands of ‘prophets of longevity,’ some of whom have gone so far as to predict that ‘we will lick the problem of aging completely, so that accidents will be essentially the only cause of death.’ Lasch was unsparing in his indictment of these experts: such thinking, as Lasch saw it, was ‘futurology’ without any grasp of a morally compelling future, one that required ‘a genuine concern for posterity.’ ‘Pathological in its psychological origins and inspiration, superstitious in its faith in medical deliverance, the prolongevity movement expresses in characteristic form the anxieties of a culture that believes it has no future.’”

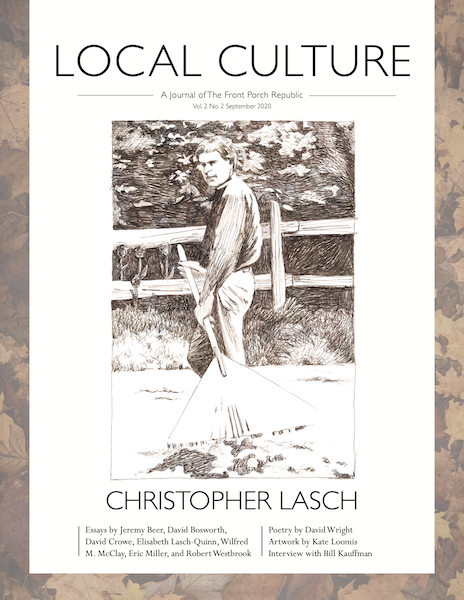

— from Robert Westbrook, “Christopher Lasch: Death and Dying in a Front Porch Republic,” Local Culture, Vol. 2, No. 2 (September 2020)