“[H]igh tech, like any human artifact, is not culturally tasteless, odorless, colorless. It contains attitude, mind-set, philosophy; and with geeks, the attitude, mind-set, and philosophy is libertarianism, in many-blossomed efflorescence. The libertarian-technology axis has been solidly in place long enough that the phrase ‘a self-described neopagan libertarian who enjoys shooting automatic weapons’ required no further explanation when it appeared as part of a technology news feature in an April 1998 issue of the online magazine Salon. A Wall Street Journal front-page feature by Gerald Seib in June 1998 described how ‘by wading into the world of computers, federal trustbusters also have waded into the country’s foremost hotbed of libertarian political activism.’ Northern California’s high tech community is a libertarian psychographic hot zone, and this guy’s mate-quest had to be the Real Deal.

“Yet high tech’s dominant libertarian mind-set is less well known than the obvious wealth and new ways of living and working it keeps spinning off — and, upon close inspection, is also far less appealing. It’s a pervasive weltanschauung, ranging from the classic eighteenth-century liberal philosophy of that-which-governs-best-governs-least love of laissez-faire free-market economics to social Darwinism, anarcho-capitalism, and beyond. It manifests itself in everything from a rebel-outsider posture common in high tech (I program, I attend raves, and I practice targetshooting with the combat shotgun on weekends) to an embarrassing lack of philanthropy (unless it involves the giving away of computers). The technolibertarian stance can be well thought out or merely a kind of reflexive guild membership (all my geek friends and coworkers think like this, so why not join the fun?).

“My fascination, mongoose-to-cobra style, with the romance between libertarianism and high tech has existed for quite a while. I was first startled by what I’ve come to call technolibertarianism when I started knocking around high tech in the early 1980s. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I have spent most of my adult life, most liberal-arts flakes ineluctably end up working with computers, because that’s where the jobs are. So it was for me back in 1981, a few years out of UC-Berkeley with a degree in psycholinguistics, a smattering of acting classes, a lot of waitressing, and a few crabbed little published poems to my name. Initially, the geek-world I was running into seemed peopled with characters very like the familiar Cal Tech/Jet Propulsion Lab/Southern California aerospace guys I fondly recollected from my childhood in Pasadena. There, the engineers and scientists more likely than not shared a vaguely New Deal mentality. They were of a generation that had seen what good things the government could do, from winning World War II to putting a man on the moon. And even if some were strong on anticommunism, conservative rather than liberal, they believed that the government could do great and good things. The unspoken cultural assumption was that progress in our shared civilization was helped along by government programs supporting scientific research, public health, education, and the bringing of electricity and telephony to rural areas. And if quizzed, these technologists would probably all have agreed that there was a shared civilization worth fostering, for geek and nongeek, rich and poor.

“On first inspection, the 1980s and 1990s nerds as people didn’t appear that different from the ones I’d known as a kid. But I came to realize that their values, politics, and orientation to the world were very very different from those of the benign guys in my childhood who, yes, actually had carried slide rules and worn pocket-protectors, as no one in hightech actually does now. It took many years of personal observation — while I moved from technical-writer positions at software firms to staff positions at computer magazines to, starting in 1989, freelance gigs for high tech corporations and for the glossy, glamourous high tech style sheet Wired — to piece together a picture of an emergent social and political subculture, one that can seem dangerously naive and, at its worst, downright scary.

“Attending technical conferences and trade shows, getting to know and making friends with computerists, eavesdropping and reading, I was trying to make sense of the libertarianism I found all around. The belief systems I ran into were confusing, for this passionate libertarian population has for the most part only experienced good things, and not bad, from government. And they were disturbing, for beneath them I sensed nastiness, narcissism, and lack of human warmth, qualities that surely don’t need to be hardwired into the fields of computing and communications. . . .

“An essay I wrote for Mother Jones magazine in July 1996 articulated more directly my unease with technolibertarianism and focused on the aggressive lack of philanthropy in high tech and the contempt for government when government had been so very verrry good to high tech. As I wailed,

Without government, there would be no Internet. . . . Further there would be no microprocessor industry, the fount of Silicon Valley’s prosperity (early computers sprang out of government-funded electronics research). There would also be no major research universities cranking out qualified tech workers: Stanford, Berkeley, MIT, and Carnegie-Mellon get access to state-of-the-art equipment plus R&D, courtesy of tax-reduced academic-industrial consortia and taxpayer-funded grants and fellowships.

“High tech’s animosity toward government and regulation goes beyond the animosity that exists in most of the general population and is stridently opposed to other views.

“‘Cyberselfish,’ the essay, is tied for first place on my life list in terms of the amount of email generated by something I’ve written. It seemed to have externalized the dismay other folks have felt with this high tech political culture. It flew around the Internet and got me interviews on radio and speaking gigs at conferences — yet was also the first thing I have ever written that got me flamed (Netspeak for being the object of electronic vituperation.) ‘Cyberselfish’ achieved a modest amount of net.fame; two Usenet groups (the Internet’s public electronic chat forums) devoted themselves to trashing the piece and questioned my personal and professional integrity, which only shows the state folks get themselves into when their religion, masquerading as politics, gets attacked. Libertarianism on the Net, in spite of more than twenty years of government support for the Net’s creation and development, is a seed culture that continues to self-propagate for intellectual generation after generation.

“ОТОН (Internet acronym for On The Other Hand), that same Mother Jones essay got me responses from young people working in what’s known as South Park [i.e., the San Francisco epicenter of late ’90s tech startups], saying they had never heard this counterversion of reality before. It seemed to address the vague disquiet they had been feeling about the grim fairy tales of Big Bad Government versus the unlimited free market. Prosperity, goodness, and health were supposed to be everyone’s destiny once Toffler Second-Wave old-and-in-the-way Machine Age bureaucrats got out of the way. These South Parkers had been wondering if what they had been promised would turn out to be Potemkin villages for a new age, and, to mix metaphors, though not countries, if that Mother Jones essay was samizdat, Voice of America broadcast, circa 1957. It’s as if naming the demon — technolibertarianism — drained it of some of its power, much as in psychotherapy, the first step toward solving a problem consists of observing it and describing it.

“And the demon does have plenty of power. It was the inspiriting force behind Wired under its original owners, when it was the Playboy/Rolling Stone/Vogue for twenty-first-century digital boys (in spirit, if not the flesh), tastemaker/marker of this culture. Part of the magazine’s transgressive sexiness historically stemmed from its sassy enraged libertarianism: What adolescent male (in thought, if not biological fact), the original target in sensibility (bratty, precocious for the magazine), doesn’t want to rebel against nannies, even in the form of the Nanny State?

“When I have run into liberal elder statesmen and women of high tech — meaning people over the age of thirty — they sigh with only a small amount of hope and a great deal of resignation when I say I am trying to document high tech’s default political culture of libertarianism. Like weary Resistance fighters too long without succor, they have almost given up speaking out against the consensus reality in which they live and work. Libertarianism is a computer-culture badge of belonging, and libertarians are the most vocal political thinkers and talkers in high tech.”

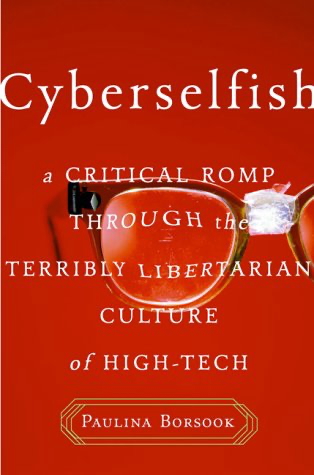

— from Paulina Borsook, Cyberselfish: A Critical Romp through the Terribly Libertarian Culture of High-tech (PublicAffairs, 2000)

An interview with Pauline Borsook, recorded in 2000, was re-published in the Friday Feature of January 24, 2025.

An interview with the president and co-founder of WIRED Jane Metcalfe was heard on Volume 7 of the Mars Hill Tapes and has been re-issued as an Archive Feature.