In a review essay published in Harper’s in November 1984, historian Christopher Lasch examined the ways in which an ideologically driven critique of nostalgia “serves, as effectively as nostalgia itself, as a form of escapism. It shares with nostalgia an eagerness to proclaim the death of the past and to deny history’s hold over the present. Those who celebrate the death of the past and those who mourn it both take for granted that our age has outgrown its childhood. Both find it difficult to believe that history still haunts our enlightened, disillusioned maturity.”

Lasch observed that the word “nostalgia” had become a fixture in the “vocabulary of political abuse.” Among the scholars and pundits whose opinions about nostalgia he reviewed were Marshall Berman, Richard Louv, Richard Hofstadter, Alvin Toffer, Fred Davis, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.. The “nostalgic American,” wrote Lasch, “served liberals as an ideal whipping boy at a time when the intellectual foundations of liberalism were beginning to erode. As the dogma of progress became increasingly untenable, the ‘party of hope’ salvaged something of its self-confidence — the appearance if not the substance of hope — by deploring the nostalgic mood that allegedly made so many Americans afraid to face the future. By the early sixties, the denunciation of nostalgia had become a liberal ritual, performed, like all rituals, with a minimum of critical reflection.”

Lasch was as critical of the lack of critical reflection by those who enjoyed nostalgia as he was of those who deplored it. As he argues at the end of the article, “Nostalgia neither provides a necessary sense of continuity in a time of rapid change nor serves as unadulterated escapism. It evokes the past only in order to bury it alive. The atmosphere of sentimental regret with which it surrounds the past has the effect of denying the past’s inescapable influence over the present. All of us, both as individuals and as a people, are shaped by past events more than we can fully understand: and never more decisively than when we think we have put those events behind us. Just when we think we have disentangled ourselves from the web of associations that forms our personal and collective identity, some unbidden memory, some obsession or compulsion, some reactivation of former distress, some reversion to habits we assumed we had outgrown reminds us that none of us enjoys the freedom to ‘create our own identity,’ in the jargon of popular psychology. Except within limits severely circumscribed, we cannot choose what we wish to become or even what we wish to remember. Memories that cause us pain can only be repressed, never banished altogether, and they control us most of all when we think we have managed to forget them. It is the knowledge of our dependence on the past that nostalgia and anti-nostalgia alike seek to repel.

“One of the delusions peculiar to our age is that we can manipulate the past to suit our immediate purposes and that having freed ourselves from the influence of cultural traditions, we can adopt an eclectic approach to history, appropriating whatever we need in order to piece together a ‘usable past.’ The ‘postmodern’ revival of earlier styles in art, architecture, popular music, and dress serves not to bring them back to life but precisely to exaggerate our distance from them. It is only when they are believed safely dead that earlier styles become eligible for restoration, not as landmarks in a continuing tradition but as historical curiosities, objects of a kind of attention that mingles affection and condescension. Revivals deny any living link with past objects. They endow those objects with the charm of distance and inconsequence. Our sense of discontinuity is now so great that even very recent periods, like the fifties or the sixties, have become objects of nostalgic retrospect. Eager to deny that events in those decades continue to haunt our politics and our culture, we consign them to the irrelevance of the good old days.

“The ‘nostalgia boom’ of the seventies first took shape as a media promotion, a non-event that proclaimed the demise of the sixties — of protest marches, riots, and countercultures. When the editors of Time in 1971 asked Gore Vidal to explain ‘the meaning of nostalgia,’ he replied, ‘It’s all made up by the media. It’s this year’s thing to write about.’ I see no reason to dispute this assessment. Vidal may have underestimated the subject’s staying power, but he was right in thinking that the media are far more interested in nostalgia than ordinary men and women. This is because ordinary men and women live in a world in which the burden of the past cannot easily he shrugged off by creating new identities or inventing usable pasts. Ordinary men and women are much more obviously and inescapably prisoners of circumstance than those who set cultural fashions. These circumstances include the constraints of inherited poverty, parental religion, and ethnic identification, and in many cases the inherited experience of racial or ethnic persecution. Trapped in a past not of their making, most people cannot afford the illusion that tradition counts for nothing, even if much of their energy goes into a struggle against it.

“Only those who have escaped from the ghetto, the small town, or the farm can believe that they no longer carry the weight of a personal and collective history. Because it is difficult for those who command the mass media, and increasingly for the educated classes in general, to imagine a past that is continuous with the present, they swing between nostalgia and a violent condemnation of nostalgia, both of which betray the same sense of dislocation. Highly susceptible to nostalgia themselves, they are quick to condemn it in others.

“Whether pining for things past or rebuking others for this fault, the educated classes seek to avoid any painful reckoning with the historical record from which they think they have liberated themselves. Unfortunately for their peace of mind, the legacy of unsolved social and political problems makes such a reckoning more and more difficult to postpone.”

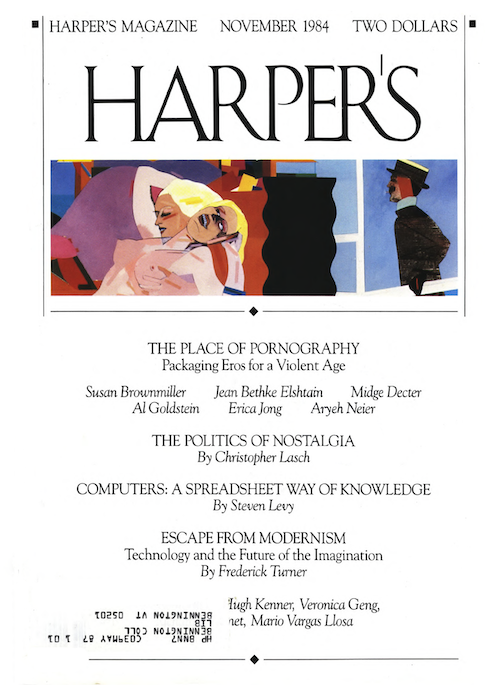

— from Christopher Lasch, “The Politics of Nostalgia,” Harper’s, November 1984, pp. 65–70.

Related reading and listening

- The life of the city in poetry — FROM VOL. 1 Ken Myers talks with W. H. Auden’s biographer and literary executor, Edward Mendelson, about political and social themes in Auden’s poetry. (7 minutes)

- The theological significance of current events — FROM VOL. 65 George Marsden discusses how Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) understood world history and the American experience. (14 minutes)

- Countering American apathy toward history — FROM VOL. 124 Historian John Fea discusses how American and Protestant individualism continues to influence our orientation toward the past. (22 minutes)

- Virgil and purposeful history — In this lecture from June 2019, classical educator Louis Markos examines Book II of The Aeneid to argue that Virgil had an eschatological view of history. (68 minutes)

- Only a dying civilization neglects its dead — Historian Dermot Quinn discusses the work of fellow historian Christopher Dawson (1889–1970). (15 minutes)

- Christopher Dawson: Chronicler of Christendom’s Rise and Fall — Dermot Quinn discusses historian Christopher Dawson’s meta-historical perspective and his wisdom about what makes cultures healthy or unhealthy. (54 minutes)

- From democracy to bureaucracy — Historian John Lukacs on the challenges of living at the End of an Age

- Ideas and historical consequences — Historian John Lukacs (1924–2019) discusses the relationship between institutions and character, popular sentiment versus public opinion, the distinction between patriotism and nationalism, and the very nature of studying history. (36 minutes)

- The historian’s communal role as storyteller — FROM VOL. 127 Historian Christopher Shannon discusses how American academic historical writing presents a grand narrative of progressivism, which it defends by subscribing to an orthodoxy of objective Reason. (21 minutes)

- Three historians on history — FROM VOL. 31

This Archive Feature presents interviews with three historians who discuss changes in historical studies. (33 minutes)

- Life without limits? — Robert Westbook on Christopher Lasch’s critique of the modern rejection of limits

- Infrastructures of addiction — Christopher Lasch on the subversive effects of the expectation of novelty

- A prophetic pilgrim — Historian Eric Miller charts Christopher Lasch’s intellectual journey in search of a vision that could direct Americans toward the higher hopes and nobler purposes that might lead to a flourishing common life. (57 minutes)

- “How deep the problems go” — FROM VOL. 103Eric Miller discusses the late historian and social critic Christopher Lasch’s intense commitment to understand the logic of American cultural confusion. (20 minutes)

- The de(con)struction of the humanities (and of truth) — Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb on the skeptical tendencies of the postmodern academy

- Christ, the key to human meaning — Gil Bailie on how the coming of Christ affirmed the intelligibility of human history (and why the abandonment of Christ invites unreason)

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 159 — FEATURED GUESTS:

Kirk Farney, Andrew Willard Jones, James L. Nolan, Jr., Andrew Kaethler, Peter Ramey, and Kathryn Wehr

- Before Church and State — Andrew Willard Jones challenges some of the conventional paradigms of thinking about political order, arguing that modern assumptions of the relationship between Church and state color how we understand history. (54 minutes

- The consequential witness of St. Patrick — Thomas Cahill describes how the least likely saviors of Western heritage, the Irish, copied all of classical and Christian literature while barbarians rampaged through the rest of Europe. (16 minutes)

- Analyzing the current indictment of Christopher Columbus — Robert Royal offers thoughtful listeners an alternative to the ignorant and heated indictment of Christopher Columbus that has become fashionable in recent months. (22 minutes)

- Forgotten lessons from Christopher Lasch — Ken Myers reads an editorial that Jason Peters wrote to introduce Local Culture magazine’s exploration of historian and social critic Christopher Lasch’s thought. (31 minutes)

- John Lukacs, R.I.P. — Historian John Lukacs discusses the vocation of studying history and how it is more a way of knowing human experience than it is a science. (23 minutes)

- Remembering Christopher Lasch — Dominic Aquila, Eric Miller, and Jeremy Beer describe the unique intellectual and moral contributions of Christopher Lasch. (26 minutes)

- Christopher Lasch: “Conservatism against Itself” — In this early article from First Things, historian Christopher Lasch poses the question of whether cultural conservatism is compatible with capitalism. (42 minutes)

- Jeremy Beer: “On Christopher Lasch” — Jeremy Beer describes the intellectual trajectory of cultural historian Christopher Lasch, who critiqued the modern “anxiously narcissistic” self and the culture that produced it. (55 minutes)

- The burden of creating meaning — George Parkin Grant on the insatiability of the modern will

- Word becomes flesh, Reality becomes fact — Henri de Lubac on the Incarnation and history

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 124 — FEATURED GUESTS:

John Fea, Robert F. Rea, John C. Pinheiro, R. J. Snell, Duncan G. Stroik, Kate Tamarkin, and Fiona Hughes

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 114 — FEATURED GUESTS: Susan Cain, Brad S. Gregory, David Sehat, Augustine Thompson, O.P., Gerald R. McDermott, and Marilyn Chandler McEntyre

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 103 — FEATURED GUESTS: Steven D. Smith, David Thomson, Adam McHugh, Glenn C. Arbery, Eric Miller, and Eric Metaxas

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 100 — FEATURED GUESTS: Jennifer Burns, Christian Smith, Dallas Willard, Peter Kreeft, P. D. James, James Davison Hunter, Paul McHugh, Ted Prescott, Ed Knippers, Martha Bayles, Dominic Aquila, Gilbert Meilaender, Neil Postman, and Alan Jacobs

- Digital equality and the untuning of the world — Lee Siegel analyzes how web-based pursuits of unique identity is so unbounded that personal definition becomes impossible.

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 87 — FEATURED GUESTS: John Witte, Jr., Steven Keillor, Philip Bess, Scott Cairns, and Anthony Esolen

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 84 — FEATURED GUESTS: Harry L. Lewis, Nicholas Wolterstorff, Brendan Sweetman, James Turner Johnson, David Martin, and Edward Ericson, Jr.

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 77 — FEATURED GUESTS: Eric Miller, Lisa de Boer, Peter J. Schakel, and Alan Jacobs

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 75 — FEATURED GUESTS: Mark Malvasi, John Lukacs, Steve Talbott, Christian Smith, Eugene Peterson, and Rolland Hein

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 53 — FEATURED GUESTS: Lawrence Adams, Dana Gioia, Elmer M. Colyer, R. A. Herrera, Margaret Visser, and Joseph Pearce