What makes sense to technolibertarians “is a delta-world (change of a certain kind defines certain units of scientific measurement) that maps onto engineering reality (you fix the bug, improve the product, bring out a new model). The delta-world is one of management by quarterly reports, Web Weeks, and day-trading. Whether this maps well onto all aspects of human breathing or striving is something else.

“Virginia Postrel, longtime editor in chief of Reason magazine, sort of the Nation/New Republic/Atlantic Monthly of libertarianism, gets at this delta-world ideal in her ‘Dynamism, Diversity, and Division in American Politics’ speech, which she delivered at the Fifth Annual Bionomics Conference in 1996 — and which was subsumed in her 1998 book, The Future and Its Enemies: The Growing Conflict on Creativity, Enterprise, and Progress. She made good points about how the Jeremy Rifkins and Patrick Buchanans of the world have more in common with each other than, say, with their more obvious political allies. She sees folks like Rifkin and Buchanan as agents of stasis who either long for a fantasy past or want to plan (code for control-freaking/bureaucratizing/anti-individualist acting) for a better future; on the other hand, agents of dynamism believe in

the complex ecology of human beings . . . preferring decentralized choice. . . . They are open-ended… Nobody — no individual, no governing group — knows enough about a society to manage it in detail . . . . Dynamism is harder to understand than stasis. . . . It is the product of millions of unplanned choices directed by no central person or organization. . . . Popular culture . . . religion . . . the family . . . they are complex systems that do not stay put, spontaneous orders subject to no one’s control. . . . Dynamic systems not only accommodate diversity; their flexibility allows them to accommodate external change. They are resilient. When the world changes, they permit many small-scale experiments, increasing the chances of success and decreasing the consequences of failure. They allow fine-tuning.

“It sounds great. Who would not want to be on the side of dynamism? Wired magazine celebrated its sixth anniversary with an entire issue devoted to the proposition that ‘Change Is Good’ (emblazoned on the front cover). Myself, I’m so glad that I live in an era of photocopiers, laptops, call-waiting, Telfa pads, Advil, and narrow-spectrum antibiotics.

“But I don’t think all change is good, or without cost. I am a Luddite — in the true sense of the word. The followers of Ned Ludd were rightfully concerned that rapid industrialization was ruining their traditional artisanal workways and villages, creating nineteenth-century local environmental disasters and horror-show factory working (and living) conditions for family members of all ages. For decades, the displacements of the Industrial Revolution sent hundreds of thousands of people to lives of penury, starvation, disease, and despair in the slums of big cities. The Luddites were early labor and ecology activists, upset not so much with technology per se but with technology’s destructive effects to their bodies, to their children, to the places where they lived, to their ability to make a sane living. And, in a sense, they were early protesters of de-skilling.

“De-skilling is not a purely late-twentieth-century phenom (where reliance on computers means that people with less skill and knowledge — who can be paid far less — perform previously more-skilled jobs). Considering the failure of so many modern buildings (in design, execution, defect of materials, workmanship), isn’t it worth questioning whether kids straight out of an architecture program, slaved to CAD/CAM workstations and paid relatively little, are doing as good a job as the senior architect, who has knowledge not so containable in commercial software, they displaced? So the Luddites smashed mechanical looms, the symbols and agents of their oppression, and have had an unfair bad rap ever since as loons and barbarians. Not to romanticize the agrarian past, but much of urban and small-factory-town life of the Industrial Revolution was very much like that of Blake’s dark Satanic mills. Technology and trade marched on and global empires were created; monopolies arose; it all sounds familiar.

“Yes, a middle class sprang from this industrialization, and it certainly made possible the improved standard of living a century later for North Americans and Western Europeans; but that dynamism of the nineteenth century was hardly without grievous cost. In this model of how the world works or should work, there’s the spirit of Lenin: In regard to revolution, you have to break eggs to make an omelet. Or maybe the model is biological: Nature has her own cycles of creation and destruction, and who are we to argue?

“Like the Luddites, I am not so sure most change benefits most people. Postrel’s spectrum from stasis to dynamism (with sense and sensibility heavily weighted on one side of that spectrum) ignores all the largely invisible stable societal structures (just to name two: (1) public investment in sanitation, education, and public water-ways; (2) changes in common law that made it legal for women to vote and own property) that make all this dynamism productive and possible. Contrast this with the lack of centralized authority that was so dreadfully inconveniencing in the recent unpleasantness in the Balkans. The changing world Postrel refers to often changes for the better because its governments change.”

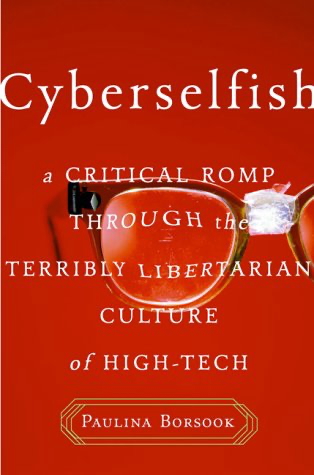

— from Paulina Borsook, Cyberselfish: A Critical Romp through the Terribly Libertarian Culture of High-tech (PublicAffairs, 2000)

An interview with Pauline Borsook, recorded in 2000, was re-published in the Friday Feature of January 24, 2025.

Related reading and listening

- The downward spiral of all technocracies — Andrew Willard Jones explains the two paths that exist with the development of new technologies: one which leads to an expansion of the humane world and one which exploits and truncates both Creation and humanity. (65 minutes)

- In technology, we live and move and have our knowing — George Parkin Grant on technology’s establishment of a framework for thinking about technology

- On the Degeneration of Attentiveness — Critic Nicholas Carr talks about how technology-driven trends affect our cultural and personal lives. (56 minutes)

- Gratitude, vitalism, and the timid rationalist — In this lecture, Matthew Crawford draws a distinction between an orientation toward receiving life as gift and a timid and cramped rationalism that views man as an object to be synthetically remade. (52 minutes)

- Humans as biological hardware — In this essay, Brad Littlejohn and Clare Morell decry how modern technology tends to hack the human person in pursuit of profit. (55 minutes)

- Choices about the uses of technology — This Feature presents interviews with David Nye and Brian Brock related to how we evaluate adoption of new technology and how technology influences our thinking. (31 minutes)

- The libertarian spawning-ground of tech bros — Paulina Borsook on high tech’s long-standing animosity toward government and regulation

- Tech bros and public power — Paulina Borsook discusses the “bizarrely narcissistic” and ultra-libertarian culture of Silicon Valley. (22 minutes)

- Voluntarily silencing ourselves — FROM VOL. 39 John L. Locke discusses the value of personal communication and how technology is displacing it. (12 minutes)

- Life in a frictionless, synthetic world — FROM VOL. 17 Mark Slouka explores the worldview of techno-visionaries who aim to create a new era of human evolution. (11 minutes)

- The digital revolution and community — FROM VOL. 7 Ken Myers talks with Jane Metcalfe, the founder of WIRED Magazine, about technology and community. (8 minutes)

- Paradoxical attitudes toward plastic — Jeffrey Meikle traces the technological, economic, and cultural development of plastic and relates it to the American value of authenticity. (15 minutes)

- Technology and the kingdom of God — FROM VOL. 63 Albert Borgmann (1937–2023) believes Christians have an obligation to discuss and discern the kind of world that technology creates and encourages. (12 minutes)

- The recovery of true authority for societal flourishing — Michael Hanby addresses a confusion at the heart of our current cultural crisis: a conflation of the concepts of authority and power. (52 minutes)

- A fearful darkness in mind, heart, and spirit — Roberta Bayer draws on the work of George Parkin Grant (1918–1988) to argue that our “culture of death” must be countered with an understanding of reality based in love, redemptive suffering, and a recognition of limitations to individual control. (33 minutes)

- Questioning “conservatives” — John Lukacs asserts that believers in unending technological ‘progress’ can’t really be conservatives.

- Living into focus — As our lives are increasingly shaped by technologically defined ways of living, Arthur Boers discusses how we might choose focal practices that counter distraction and isolation. (32 minutes)

- Albert Borgmann, R.I.P. — Albert Borgmann argues that, despite its promise to the contrary, technology fails to provide meaning, significance, and coherence to our lives. (47 minutes)

- Art as aestheticism, love as eroticism, politics as totalitarianism — Augusto Del Noce on the “technological mindset” and the loss of the sense of transcendence

- The consoling hum of technological society — Jacques Ellul on the danger of confusing “technology” with “machines”

- What happens when the Machine stops? — David E. Nye provides a context for evaluating the prospect of life in the Metaverse

- Technological choices become culture — David E. Nye insists that societies do have choices about how they use technologies, but that once choices are made and established both politically and economically, a definite momentum is established. (19 minutes)

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 141 — FEATURED GUESTS:

Grant Wythoff, Susanna Lee, Gerald R. McDermott, Carlos Eire, Kelly Kapic, and James Matthew Wilson

- The priority of paying attention — Maggie Jackson talks about the increased relevance of her 2008 book Distracted: The Erosion of Attention and the Coming Dark Age (15 minutes)

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 130 — FEATURED GUESTS:

Jacob Silverman, Carson Holloway, Joseph Atkinson, Greg Peters, Antonio López, and Julian Johnson

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 129 — FEATURED GUESTS:

Nicholas Carr, Robert Pogue Harrison, R. J. Snell, Norman Wirzba, Philip Zaleski, Carol Zaleski, and Peter Phillips

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 116 — FEATURED GUESTS: Stratford Caldecott, Fred Bahnson, Eric O. Jacobsen, J. Budziszewski, Brian Brock, and Allen Verhey

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 111 — FEATURED GUESTS: Siva Vaidhyanathan, John Fea, Ross Douthat, Ian Ker, Larry Woiwode, and Dana Gioia

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 105 — FEATURED GUESTS: Julian Young, Perry L. Glanzer, Kendra Creasy Dean, Brian Brock, Nicholas Carr, and Alan Jacobs

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 100 — FEATURED GUESTS: Jennifer Burns, Christian Smith, Dallas Willard, Peter Kreeft, P. D. James, James Davison Hunter, Paul McHugh, Ted Prescott, Ed Knippers, Martha Bayles, Dominic Aquila, Gilbert Meilaender, Neil Postman, and Alan Jacobs

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 96 — FEATURED GUESTS: David A. Smith, Kiku Adatto, Elvin T. Lim, David Naugle, Richard Stivers, and John Betz

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 94 — FEATURED GUESTS: Maggie Jackson, Mark Bauerlein, Tim Clydesdale, Andy Crouch, and Jeremy Begbie

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 89 — FEATURED GUESTS: Jerome Wakefield, Christopher Lane, Dan Blazer, Fred Turner, Barrett Fisher, and Thomas Hibbs

- Better things for better living — Richard DeGrandpre: “When a thousand points of light shine upon you in a commercial war for your thoughts, feelings, and wants, your mind adapts, accepts, and then, to feel stimulated, needs more.”

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 81 — FEATURED GUESTS: Nigel Cameron, Joel James Shuman, Brian Volck, Russell Hittinger, Mark Noll, and Stephen Miller

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 75 — FEATURED GUESTS: Mark Malvasi, John Lukacs, Steve Talbott, Christian Smith, Eugene Peterson, and Rolland Hein

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 48 — FEATURED GUESTS: Jon Butler, Gary Cross, Zygmunt Bauman, Pico Iyer, Richard Stivers, Larry Woiwode, Alan Jacobs, and James Trott

- The Word Made Scarce — Barry Sanders discusses teaching in the age of technology, the effects of literacy on society, and the links between illiteracy and violence. (54 minutes)