“Christopher Dawson was not a man of his time. Nor was he a period piece. Allow me to deal with the former statement first. Dawson was a late Victorian, by which I do not only mean that he was born in 1889. His childhood, his upbringing, his family, the surroundings, the climate, the atmosphere of his youth were all Victorian — in a now Arcadian and beautiful sense of that adjective. That, contra writers such as Lytton Strachey, was not a constraint but a tremendously vital asset in the lives of certain people, including the life of this otherwise unworldly man. The evidence is there in Dawson’s own ‘Memories of a Victorian Childhood,’ a beautiful piece of writing first published in this volume. It is full of precise and evocative descriptions of the houses and the counties he knew when he was a child. They include Wales, Wessex, and the West Riding of Yorkshire. His knowledge and feel for these lands, of the essence of those countrysides, are amazing proofs of the rural affections of a man who led a bookish, in many ways closed, and sometimes even an ivory-tower-tinted life. Even in the beginning of this century the climate of Dawson’s early youth was close not only to the world of Kilvert’s Diary or to Trollope’s Barchester but in some ways even to that of Jane Austen. And this, I repeat, was a very formative asset — because Dawson loved it and venerated it and sought no escape from it. There is a great difference between being a man for all seasons and being a man of one’s own time. The latter, who fits in exactly with the customs and habits, including mental customs and habits, of his own time will amount to little; he has no enduring values. That Christopher Dawson was not. He carried with himself not only a proper nostalgia (in the sense of the original Greek term: nostos + algos, a longing for home) but a tremendous inherited capital of Victorian classical learning.

“Nor was he a period piece. He belonged — or, more precisely, he contributed to — a period of Catholic intellectual revival in England, in the 1930s, together with people whose names are now, alas, unknown to an entire generation of American Catholic intellectuals: D’Arcy, Jerrold, Burns, Watkin, and others, at a time when the Chesterton and Belloc years were passing. Dawson’s mind and vision ranged wider than those of many others. He was a great historian. The evidence is there in his books and articles. That evidence is so broad and so large that in any work, book, or article attempting to interpret Dawson’s ideas the best and most apposite expositions of those ideas must be passages by Dawson himself. He once wrote, in a mildly critical article about that most pedestrian of living English modern historians Allan Bullock: ‘The academic historian is perfectly right in insisting on the importance of the techniques of historical criticism and research. But the mastery of these techniques will not produce great history, any more than a mastery of metrical technique will produce great poetry.’

“He was probably unaware that he was writing about himself. Yet he was very much aware that a largeness of vision is ‘the source of [the] creative power of any great historian.’”

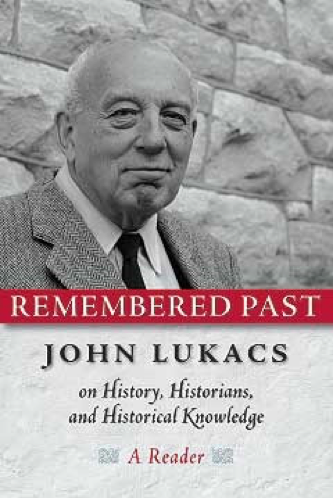

— from John Lukacs, “Review” of Christina Scott, A Historian and His World: A Life of Christopher Dawson, published in Intercollegiate Review, Spring 1992, and reprinted in Remembered Past: John Lukacs on History, Historians, and Historical Knowledge (ISI Books, 2005)