In 1963, Flannery O’Connor addressed the claim that “students do not like to read the fusty works of the nineteenth century, that their attention can best be held by novels dealing with there realities of our own time.”

“English teachers come in Good, Bad, and Indifferent, but too frequently in high schools anyone who can speak English is allowed to teach it. Since several novels can’t easily be gathered into one textbook, the fiction that students are assigned depends upon their teacher’s knowledge, ability, and taste: variable factors at best. More often than not, the teacher assigns what he thinks will hold the attention and interest of the students. Modern fiction will certainly hold it.

“Ours is the first age in history which has asked the child what he would tolerate learning, but that is a part of the problem with which I am not equipped to deal. The devil of Educationism that possesses us is the kind that can be ‘cast out only by prayer and fasting.’ No one has yet come along strong enough to do it. In other ages the attention of children was held by Homer and Virgil, among others, but, by the reverse evolutionary process, that is no longer possible; our children are too stupid now to enter the past imaginatively. No one asks the student if algebra pleases him or if he finds it satisfactory that some French verbs are irregular but if he prefers [John] Hersey to Hawthorne, his taste must prevail.

“I would like to put forward the proposition, repugnant to most English teachers, that fiction, if it is going to be taught in high schools, should be taught as a subject and as a subject with a history. The total effect of a novel depends not only on its innate impact, but upon the experience, literary and otherwise, with which it is approached. No child needs to be assigned Hersey or Steinbeck until he is familiar with a certain amount of the best work of Cooper, Hawthorne, Melville, the early James, and Crane, and he does not need to be assigned these until he has been introduced to some of the better English novelists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

“The fact that these works do not present him with the realities of his own time is all to the good. He is surrounded by the realities of his own time, and he has no perspective whatever from which to view them. Like the college student who wrote in her paper on Lincoln that he went to the movies and got shot, many students go to college unaware that the world was not made yesterday; their studies began with the present and dipped backward occasionally when it seemed necessary or unavoidable. . . . ”

“The high school English teacher will be fulfilling his responsibility if he furnishes the student a guided opportunity, through the best writing of the past, to come, in time, to an understanding of the best writing of the present. He will teach literature, not social studies or little lessons in democracy or the customs of many lands.

“And if the student finds that this is not to his taste? Well, that is regrettable. Most regrettable. His taste should not be consulted; it is being formed.”

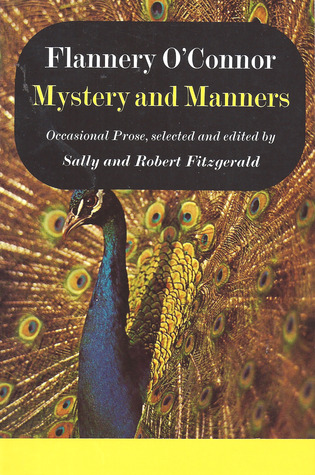

— from Flannery O’Connor’s “Total Effect and the Eighth Grade,” published in The Georgia Bulletin in 1963, reprinted in Mystery and Manners (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1961)

Related reading and listening

- Learning from experience — Flannery O’Connor on belief and experience

- Hillbilly Augustinian — Ralph Wood on Flannery O’Connor’s refusal to adapt her fiction to the national temper

- The grotesque and the transcendent — Christina Bieber Lake on why Flannery O’Connor’s readers have to work

- Flannery at 100 — In honor of Flannery O’Connor’s 100th birthday, we have gathered here an aural feast of interviews with O’Connor scholars and aficionados discussing her life, work, and faith. (3 hours, 28 minutes)

- Insights into O’Connor’s development as a writer — FROM VOL. 160 Jessica Hooten Wilson discusses her experience studying and organizing Flannery O’Connor’s unfinished third novel, Why Do the Heathen Rage? (27 minutes)

- Countering American apathy toward history — FROM VOL. 124 Historian John Fea discusses how American and Protestant individualism continues to influence our orientation toward the past. (22 minutes)

- Education that counters alienation — In this lecture, Jeanne Schindler explores how digital technologies warp not only education but our experience of being human. (30 minutes)

- Education vs. conditioning — Education necessarily involves metaphysical and theological preconditions, and Michael Hanby argues that our current education crisis is a result of society rejecting these preconditions. (41 minutes)

- Knowing by heart — D. C. Schindler reflects on Plato’s idea of “conversion” in education, assuming the symbol of the heart as the center of man. (39 minutes)

- Education as a pilgrimage and a mystery — In this lecture, James Matthew Wilson gives a compelling argument for understanding the role of a literary or poetic education as an immersion of the whole being in truth and beauty. (43 minutes)

- Submission to mathematical truth — In this lecture, Carlo Lancellotti argues that integration of the moral, cognitive, and aesthetic aspects of mathematics is needed in a robust liberal arts mathematics curriculum. (25 minutes)

- What higher education forgot — FROM VOL. 84 Harry L. Lewis discusses higher education’s amnesia about its purposes, and how that shortchanges students. (19 minutes)

- The formation of affections — FROM VOL. 101 James K. A. Smith explains how education always involves the formation of affections and how the form of Christian education should imitate patterns of formation evident in historic Christian liturgy. (15 minutes)

- A Christian philosophy of integrated education — FROM VOL. 61 Michael L. Peterson discusses how Christianity could inform society’s understandings of education and human nature. (8 minutes)

- Education for human flourishing — Co-authors Paul Spears and Steven Loomis argue that Christians should foster education that does justice to humans in our fullness of being. (23 minutes)

- The social irrelevance of secular higher education — FROM VOL. 85 Professor C. John Sommerville describes the increasingly marginal influence of universities in our society, and why they seem to be of no substantive relevance to people outside the school. (13 minutes)

- The history of Christianity and higher education — FROM VOL. 50 In tracing Christianity’s relationship to the academy, Arthur F. Holmes points to Augustine as one of the first to embrace higher learning, believing God’s ordered creation to be open to study by the rational mind of man. (9 minutes)

- In praise of a hierarchy of taste — In a lecture at a CiRCE Institute conference, Ken Myers presented a rebuttal to the notion that encouraging the aesthetic appreciation of “higher things” is elitist and undemocratic. (58 minutes)

- Prudence in politics — FROM VOL. 146

Henry T. Edmondson, III talks about Flannery O’Connor’s understanding of political life, which was influenced by a range of thinkers including Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Eric Voegelin, and Russell Kirk. (19 minutes)

- Flannery O’Connor and Robert Giroux — FROM VOL. 147 Biographer and priest Patrick Samway talks about the relationship between fiction writer Flannery O’Connor and the legendary editor Robert Giroux. (21 minutes)

- The dangers of the life of the mind — Robert H. Brinkmeyer, Jr., on why Flannery O’Connor encouraged the cultivation of “Christian skepticism”

- Remembering Miss O’Connor — Literary critic Richard Gilman shares impressions of his relationship with Flannery O’Connor

- God is in the details — Flannery O’Connor on why stories rely on the particularities of reality

- The artist’s commitment to truth — Fr. Damian Ference, author of Understanding the Hillbilly Thomist, explores the depths to which Flannery O’Connor was steeped in Thomistic philosophy. (18 minutes)

- Flannery O’Connor and Thomistic philosophy — Fr. Damian Ference explores the depths to which Flannery O’Connor was steeped in Thomistic philosophy, as evidenced by her reading habits, letters, prayer journal, and, of course, essays and fiction. (48 minutes)

- How music reflects and continues the created order — Musician, composer, and teacher Greg Wilbur explores how music reflects the created order of the cosmos. (55 minutes)

- On wonder, wisdom, worship, and work — Classical educator Ravi Jain dives deeply into the nature, purpose, and interconnectedness of the liberal, common, and fine arts. (43 minutes)

- Orienting reason and passions — In an essay titled “The Abolition of Mania” (Modern Age, Spring 2022), Michael Ward applies C. S. Lewis’s insights to the polarization that afflicts modern societies. (16 minutes)

- At the trailhead of a long trek — Jessica Hooten Wilson on the discovery of a literary remnant

- Christian education and pagan literature — Kyle Hughes on learning from Basil of Caesarea about the curricular choices for Christian educators

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 160 — FEATURED GUESTS:

Jessica Hooten Wilson, Kyle Hughes, Gil Bailie, D. C. Schindler, Paul Tyson, and Holly Ordway

- Teaching for wonderfulness — Stratford Caldecott on why education is about how we become more human, and therefore more free

- Education and human be-ing in the world — In championing a classical approach to teaching, Stratford Caldecott was an advocate for a musical education, affirming the harmonious unity in Creation. (26 minutes)

- Maintaining a connected grasp of things — Ian Ker summarizes the central concern of John Henry Newman’s educational philosophy as developed in The Idea of a University

- The university and the unity of knowledge — Biographer Ian Ker discusses John Henry Newman’s understanding the goal of “mental cultivation.” (17 minutes)

- The future of Christian learning — Historian Mark Noll insists that for Christian intellectual life to flourish, a vision for comprehensive and universal social and cultural consequences of the Gospel has to be assumed. (18 minutes)

- Earthly things in relation to heavenly realities — In this lecture, Ken Myers argues that the end of education is to train students to recognize what is really real. The things of this earth are only intelligible in light of heavenly realities. (59 minutes)

- Sustaining a heritage of wisdom — Louise Cowan (1916–2015) explains how the classics reach the deep core of our imagination and teach us to order our loves according to the wholeness of reality. (16 minutes)

- Parsing the intellectual vocation — Norman Klassen and Jens Zimmermann demonstrate that some form of humanism has always been central to the purposes of higher education, and insist that the recovery of a rich, Christocentric Christian humanism is the only way for the university to recover a coherent purpose. (39 minutes)

- Teachers and Learners — Ian Ker shares John Henry Newman’s ideals of learning, and Mark Schwehn discusses the virtues of good teachers. (27 minutes)

- Art and the truth of things — Joseph Nicolello explains the origins and themes of his imaginary dialogue between Jacques Maritain and Flannery O’Connor. (28 minutes)

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 153 — FEATURED GUESTS:

Charles C. Camosy, O. Carter Snead, Matt Feeney, Margarita A. Mooney, Louis Markos, and Alan Jacobs

- Visionary education — Josef Pieper on the mistake of confusing education with mere training

- On the re-enchantment of education — Stratford Caldecott on teaching in light of cosmic harmony

- Healthy habits of mind — Scott Newstok describes how many efforts at educational reform have become obstacles to thinking well, and he offers a rich and evocative witness to a better way of understanding what thinking is. (20 minutes)

- Mars Hill Audio Journal, Volume 151 — FEATURED GUESTS:

Richard Stivers, Holly Ordway, Robin Phillips, Scott Newstok, Junius Johnson, and Peter Mercer-Taylor

- The dismissal of standards as cultural imperialism — Rochelle Gurstein on the loss of “principled debate about the quality and character of our common world”

- Wise use of educational technologies — David I. Smith articulates the difficulties Christian schools face as they seek to use technology in a faithful way. (24 minutes)

- Educational provocations — Steve Talbott on establishing ends for education before selecting means

- The flickering of the American mind — Diana Senechal on problems of distraction in education