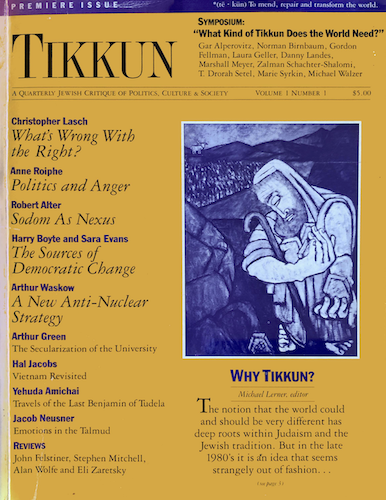

In 1986, in the middle of Ronald Reagan’s second term in office, historian Christopher Lasch wrote an article in the first issue of a new magazine called Tikkun. Described as a Jewish left-progressive quarterly — the liberal alternative to Commentary —Tikkun got its name from the Hebrew phrase, tikkun olam, “healing or restoring the world.”

Lasch’s article was titled “What’s Wrong with the Right,” and it anticipated themes in his First Things article of 1990, “Conservatism against Itself.” He began by observing that “Contemporary conservatism has a strong populist flavor, having identified itself with the aspirations of ordinary Americans and appropriated many of the symbols of popular democracy. It is because conservatives have managed to occupy so much of the ground formerly claimed by the left that they have made themselves an important force in American politics. They say with considerable justification that they speak for the great American middle class: hard-working men and women eager to better themselves, who reject government handouts and ask only a fair chance to prove themselves. Conservatism owes its growing strength to its unembarrassed defense of patriotism, ambition, competition, and common sense, long ridiculed by cosmopolitan sophisticates, and to its demand for a return to basics: to “principles that once proved sound and methods that once shepherded the nation through earlier troubled times,” as Burton Pines puts it in his “traditionalist’ manifesto, Back to Basics.”

The main theme in Lasch’s Tikkun article is that conservatives “unwittingly side with the social forces that contribute to the destruction of ‘traditional values’.” By focusing on the political commitments of those who run what is now derisively called “mainstream media,” American conservatives typically neglect to attend to the larger economic and cultural forces that undermine their own commitments. While the specific references in Lasch’s argument are dated, his underlying points are still relevant.

“The right insists that the ‘new class’ controls the mass media and uses this control to wage a ‘class struggle’ against business, as Irving Kristol puts it. Since the mass media are financed by advertising revenues, however, it is hard to take this contention seriously. It is advertising and the logic of consumerism, not anti-capitalist ideology, that governs the depiction of reality in the mass media. Conservatives complain that television mocks ‘free enterprise’ and presents businessmen as ‘greedy, malevolent, and corrupt,’ like J. R. Ewing. To see anti-capitalist propaganda in a program like Dallas, however, requires a suspension not merely of critical judgment but of ordinary faculties of observation. Images of luxury, romance, and excitement dominate such programs, as they dominate the advertisements that surround and engulf them. Dallas is itself an advertisement for the good life, like almost everything on television — that is, for the good life conceived as endless novelty, change, and excitement, as the titillation of the senses by every available stimulant, as unlimited possibility. ‘Make it new’ is the message not just of modern art but of modern consumerism, of which modern art, indeed —even when it claims to side with the social revolution — is largely a mirror image. We are all revolutionaries now, addicts of change. The modern capitalist economy rests on the techniques of mass production pioneered by Henry Ford but also, no less solidly, on the principle of planned obsolescence introduced by Alfred E. Sloane when he instituted the annual model change. Relentless ‘improvement’ of the product and upgrading of consumer tastes are the heart of mass merchandising, and these imperatives are built into the mass media at every level. Even the reporting of news has to be understood not as propaganda for any particular ideology, liberal or conservative, but as propaganda for commodities — for the replacement of things by commodities, use values by exchange values, and events by images. The very concept of news celebrates newness. The value of news, like that of any other commodity, consists primarily of its novelty, only secondarily of its informational value. As Waldo Frank pointed out many years ago, the news appeals to the same jaded appetite that makes a child tire of a toy as soon as it becomes familiar and demand a new one in its place. As Frank also pointed out (in The Re-discovery of America, published in 1930), the social expectations that stimulate a child’s appetite for new toys appeal to the desire for ownership and appropriation: the appeal of toys comes to lie not in their use but in their status as possessions. ‘A fresh plaything renews the child’s opportunity to say: this is mine.’ A child who seldom gets a new toy, Frank says, ‘prizes it as part of himself.’ But if ‘toys become more frequent, value is gradually transferred from the toy to the toy’s novelty. . . . The Arrival of the toy, not the toy itself, becomes the event.’ The news, then, has to be seen as the ‘plaything of a child whose hunger for toys has been stimulated shrewdly.’ We can carry this analysis one step further by pointing out that the model of ownership, in a society organized around mass consumption, is addiction. The need for novelty and fresh stimulation become ever more intense, intervening interludes of boredom increasingly intolerable. It is with good reason that William Burroughs refers to the modern consumer as an ‘image junkie.’

“Conservatives sense a link between television and drugs, but they do not grasp the nature of this connection any more than they grasp the important fact about news: that it represents another form of advertising, not liberal propaganda. Propaganda in the ordinary sense of the term plays a less and less important part in a consumer society, where people greet all official pronouncements with suspicion. Mass media themselves contribute to the prevailing skepticism; one of their main effects is to undermine trust in authority, devalue heroism and charismatic leadership, and reduce everything to the same dimensions. The effect of the mass media is not to elicit belief but to maintain the apparatus of addiction. Drugs are merely the most obvious form of addiction in our society. It is true that drug addiction is one of the things that undermines ‘traditional values,’ but the need for drugs — that is, for commodities that alleviate boredom and satisfy the socially stimulated desire for novelty and excitement— grows out of the very nature of a consumerist economy.

“The intellectual debility of contemporary conservatism is indicated by its silence on all these important matters. Neoclassical economics takes no account of the importance of advertising. It extols the ‘sovereign consumer’ and insists that advertising cannot force consumers to buy anything they don’t already want to buy. This argument misses the point. The point isn’t that advertising manipulates the consumer or directly influences consumer choices. The point is that it makes the consumer an addict, unable to live without increasingly sizeable doses of externally provided stimulation and excitement. Conservatives argue that television erodes the capacity for sustained attention in children. They complain that young people now expect education, for example, to be easy and exciting. This argument is correct as far as it goes. Here again, however, conservatives incorrectly attribute these artificially excited expectations to liberal propaganda — in this case, to theories of permissive childrearing and ‘creative pedagogy.’ They ignore the deeper source of the expectations that undermine education, destroy the child’s curiosity, and encourage passivity. Ideologies, however appealing and powerful, cannot shape the whole structure of perceptions and conduct unless they are embedded in daily experiences that appear to confirm them. In our society, daily experience teaches the individual to want and need a never-ending supply of new toys and drugs. A defense of ‘free enterprise’ hardly supplies a corrective to these expectations.”

— from Christopher Lasch, “What’s Wrong with the Right,” Tikkun, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Jan. 1986), pp. 23–29.